Haddonfield Memorial High School Case Study on Mentorship

How Mentorship Is Improving the Mental Health of AAPI Students at New Jersey’s Haddonfield Memorial High School. In 2019, Haddonfield High hired four...

6 min read

Care Solace Sep 14, 2023 9:28:54 AM

A 35:1 student-to-teacher ratio makes paying close attention to each student’s unique needs seem impossible. The teacher at the front of the classroom is just one person, after all — and they have little time and a lot of material to cover. How, then, does that teacher ever build a student-centered classroom? Is being student-centered just a nice theory in education? Or can we actually turn the theory into a sustainable practice in individual classrooms and entire school communities?

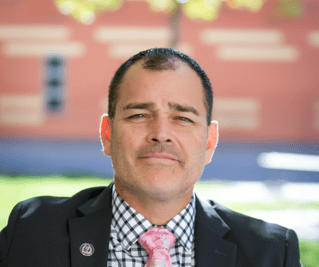

Jose Luis Navarro, Coach/Consultant at The Navarro Group, cares deeply about finding answers to these questions. He’s spent much of his professional life experimenting — and succeeding — with methods for making schools student-centered. He recently shared his philosophy and methodology with Care Solace.

Care Solace: Mr. Navarro, you’re National Board Certified, and you were named California Teacher of the Year in 2009 and Los Angeles Times Latino Educator of the Year in 2013. All this time, you’ve delivered a consistent message.

Jose Luis Navarro: That’s true. Sometimes it gets frustrating to be saying the same thing for so long. But I can’t stop. We need to revolutionize education.

CS: What do you mean by revolutionize?

JLN: I don’t mean we need to recklessly buck the system — I’m not interested in some kind of a coup. The kind of revolution I’m calling for is primarily an individual one. Many of us need to reconnect to the reason why we are in education in the first place by reaffirming our core values. And then we need to bring our day-to-day choices in better alignment with those values.

That is a radical act for each and every one of us, no matter how long we’ve been in the front of a classroom, no matter how many papers we’ve graded in our lifetime.

CS: You talk about systematizing your values. Are we talking about our own personal values as educators? Or are we talking about the articulated values of our individual schools?

JLN: Ideally, those values are one and the same, so there is real interest convergence between the school and those who work in the school. Your values need to be part of your school’s DNA and woven into its systems.

For example, if I say we're a student-centered school, listening to students’ voices is a value. Do we have any mechanisms to do that? In my school, we mechanize that value with surveys and a student brain trust, my cabinet, if you will. I regularly ask the students in that cabinet how they feel about our school’s plans — and I listen to what they think.

CS: What are your most deeply-held values?

JLN: Love, compassion, and curiosity drive me — these values have always been my fuel. Here’s why: Only with love for our students can we build relationships and community. Only with compassion can we really see the human beings in front of us. And only with sincere and insatiable curiosity will we be motivated to ask the right questions, connect the dots, and find hacks to kids’ hearts and minds.

CS: So let’s talk about how you “systematize” love to make your school student-centered.

JLN: We always lead with love. In order for real change to happen in our classrooms and in our students, this value must be first and last. Why would students believe anything we say if we don't lead with love?

The love you feel for your students may be the reason you get up in the morning, but even then, you may not be expressing that love in the most effective ways. When we know our students’ love language, we can begin to recognize them in a way they appreciate and motivate them in a way that works for them.

CS: You’re talking about the 5 Love Languages, which people may assume is just useful for couples. But you use the love languages to communicate with students better.

JLN: Yes, our freshmen take a survey. When we know a student’s love language is quality time, we can give them 5 minutes of our full attention. We can put a little extra thought into written or verbal comments to a student whose love language is words of affirmation. And there are many ways we can speak to students whose love language is physical touch, acts of service, or gifts.

It’s up to us to create a system that’s “multilingual,” so we actually have a shot at making legitimate connections with our students.

CS: What about compassion? We tend to think of that as purely a feeling — not something we can mechanize.

JLN: Compassion gives us the ability to see the fullness of each and every human being in our classrooms — and what those human beings lack but desperately need in order to learn. Compassion never lets us forget that it’s hard for a kid to see the whiteboard with fear, poverty, or trauma in their way.

If your school is really student-centered, you’ll bear in mind Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and compassionately and creatively find ways to meet those needs. That’s how we can mechanize and mobilize compassion.

.png)

CS: So, you’re referring to the pyramid: physiological needs at the bottom, and safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization layered on top of that. An individual moves through them as stages.

JLN: Schools can help that process. We can meet physiological needs through facilities like clean, safe bathrooms and nutritious food. We can create a physically safe environment by having security measures. Emotional safety can be achieved through mindfulness practices. Some pretty tough kids ease into quiet breaths when given the space and opportunity. And when they need more mental health support than our schools can provide, we can let Care Solace take the wheel.

We can promote self-esteem with student steering committees, like I mentioned before — my cabinet. And we can grow love and belonging with mentorship. Good mentors know and speak the love languages of their mentees.

In the context of school, self-actualization means a student is available to learn; we’ve given substantially enough toward basic needs in order to move kids up the pyramid.

CS: According to that kind of mechanized compassion model, then when kids are absent, acting out, or checked out, they’re “unavailable” to learn. And Maslow’s pyramid can help schools and educators determine what to give.

JLN: Exactly. But students unavailable for learning should make us curious, too. We should never assume we know what’s happening in our students based solely on their outward appearances, our education, or our years of experience.

We’ve got to collect and use data that directly connects to the hierarchy of needs. The data we collect should make us curious about its implications — and we should be curious enough to keep collecting more data. Data tells us the story of our students like nothing else can, and we have much potential data available to us.

CS: You collect a lot of data in a color-coded comprehensive spreadsheet, right? You track attendance, tardies, GPA, credits, discipline referrals, love language survey results, Lexile scores, Resilience and Coping Intervention (RCI) exercise results, and even Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ) survey scores.

JLN: And I’d like to add the 40 Developmental Assets survey score, which is an evaluation of positive factors for youth success, including external support from relationships and opportunities, as well as internal strengths, values, and commitments.

So what do I do with this data? Let it talk to me. The color coding is helpful, so the lowest-performing kids are easy to identify. Then I start connecting the dots.

CS: Can you give a couple of examples of how you let the data talk to you?

JLN: Student #1 has a .95 GPA and 100% attendance. Is it possible that he shows up every day because he feels safer at school than he does at home? Student #2 was a senior last year and has 277 credits. You only need 230 to graduate. What’s keeping her from moving on? Student #3 is reading at a 12.9 to college level — and he's failing. Is it possible that there’s a mental health issue that needs addressing?

Those data stories allow psychiatric social workers and teachers to be proactive. If they have 20 minutes, they know which kids to seek out. Are they rolling in knowing that student’s love language so they can have effective engagement?

CS: What do you do if you meet some resistance from staff about using data? Like, oh no. Another thing to do.

JLN: Sending emails asking for participation doesn’t work. So we have data days. There might be some resistance, but working it into the school day helps — it’s an effective way to systematize curiosity. We can look at students like the ones in the examples I just gave and get curious together about what’s going on.

I also think that counternarratives are critical, like a former student of ours who is at Stanford. An unlikely story, given that she is an El Salvadoran immigrant and came to the US on the top of a train, dressed as a little boy. How did she do that? Let’s be curious about that!

CS: So love, compassion, and curiosity. Systematize those 3 values so you have data to tell you stories that you can act on. That’s how you keep kids in the center of the school experience.

JLN: Without love, compassion, and curiosity as our core values, we may never be motivated enough to take care of physiological needs or safety and belonging needs. Then these kids can’t self-actualize.

When their basic needs are met, when they feel safe enough where they can be themselves, they’re going to shine. And we all benefit from the light.

When your love, compassion, and curiosity show you that a student needs additional mental health support, you can connect them with Care Solace. We’ll listen to their needs and connect them with just the right care, 24/7/365. Discover more about how Care Solace provides wraparound support for K-12 school districts.

Jose Luis Navarro IV is the leading Coach and Consultant at the Navarro Group. Before this, he served as the Local District North East Support Coordinator, leading innovative reforms in LDNE. Notably, he's the founding principal of the award-winning Social Justice Humanitas Academy, which won the 2015 National Community School and Teacher Powered Schools National Awards. Navarro holds several accolades, including National Board Certification, California Teacher of the Year, and Latino Educator of the Year. He's also an Adjunct Professor at California State University Dominguez Hills and a UCLA Master's Degree graduate in Education Leadership. Prior to teaching, he worked as a firefighter and a Peace Corps Volunteer. Navarro's dedication stems from the belief that all students deserve care and support, inspired by his own children.

How Mentorship Is Improving the Mental Health of AAPI Students at New Jersey’s Haddonfield Memorial High School. In 2019, Haddonfield High hired four...

“Relax and enjoy your time with family:” This is the message school staff generally hear from leadership as they prepare for the holiday break. While...

Schools are often the first line of defense in supporting student mental health and preventing youth suicide. Recognizing this responsibility,...